The Essential Dolmenwood-ness of Dolmenwood

It would be advantageous to have an idea of which elements are useful in bringing out the best in a game.

I had a mentor, in the theatre world, who told me about her theory of the elements of theatre. They were in fact, the elements of art, and what they really are is a list of human needs that art fulfills. This is fun and useful because you can look at different works of art and see how different sets of these needs being addressed. They emphasize different elements. If you’re making art, you can be selective about which of these you’re emphasizing.

That mentor was Anne Bogart. She is one of the founders of the SITI Company, and that’s just one of her many bona fides. I can’t start talking about her because I won’t stop.

Really good art, she said, succeeds at fulfilling a couple of these needs really well. Great art might make good use of several of the elements. And the greatest of all art – e.g. Shakespeare – excels at all seven.

Seven Elements of Art

This is Anne Bogart’s list of Seven Elements of Art (in no particular order) →

- Spectacle

- Participation

- Empathy

- Ritual

- Magic

- Entertainment

- Learning.

This is a list that specifically applies to theatre. It applies to paintings and dance and sculpture and prank phone calls, too. Whatever your art is, this list can be a useful set of lenses for selective perspectives.

So what about RPGs, huh? I’m not saying this list does not apply, but what would be on a list that’s more specific to RPGs. That list could be really useful for understanding the art of RPGs. To be abundantly clear – I’m not talking about the elements of RPG books or RPG rules. I’m talking about RPG sessions, the experience of playing the games.

In teaching a way of making theatre called Moment Work, we would start by asking students to make a huge list of allllllll the elements of theatre. The eventual goal was for them to see that The Text does not have to dominate the theatre-making process. Any of the elements can take the lead. And, moreso, you can make interesting and useful discoveries by intentionally putting some elements in charge that don’t usually get to be dominant.

In that exercise, as you would imagine, the list usually start with the most obvious stuff: props, scenery, costumes, lights, sound. Eventually someone gets a little clever and says “emotion,” and then the students list emotion-related words: fear, joy, laughter, tears, etcetera. After that things usually get kind of esoteric and we add a bunch of concepts and isms to the list: postmodernism, nihilism, and various social doctrines. As you can see, it’s possible to add almost anything to the list. I always liked making sure “nonsense” was on there.

One exercise that sometimes followed involved giving several groups the same little bit of script and then having them draw a word at random from the list of elements to use as their predominant element. You give them 10 minutes to work and see what happens.

Twenty minutes later you get to witness that little scene performed in six very different ways. Group A is focused on sound, so they slap their bodies and the floor and do wild things with their voices. The next group is letting laughter lead the way, so their characters are all giggling and guffawing, despite the seriousness of the dialogue. Another group pulled “duration,” and so there are long pauses between each of the lines and they draw words and gestures out to absurd lengths. And the last group is letting “nonsense” lead. They’ve shuffled all the words like a deck of cards and they’re speaking them out of order.

It’s a wonderful demonstration of what happens when you prioritize different elements of the art, and it’s like you’ve conducted six little experiments to see which brings out the best in the scene. Though that’s not the explicit goal, that’s often the effect.

Have we started talking about RPGs yet?

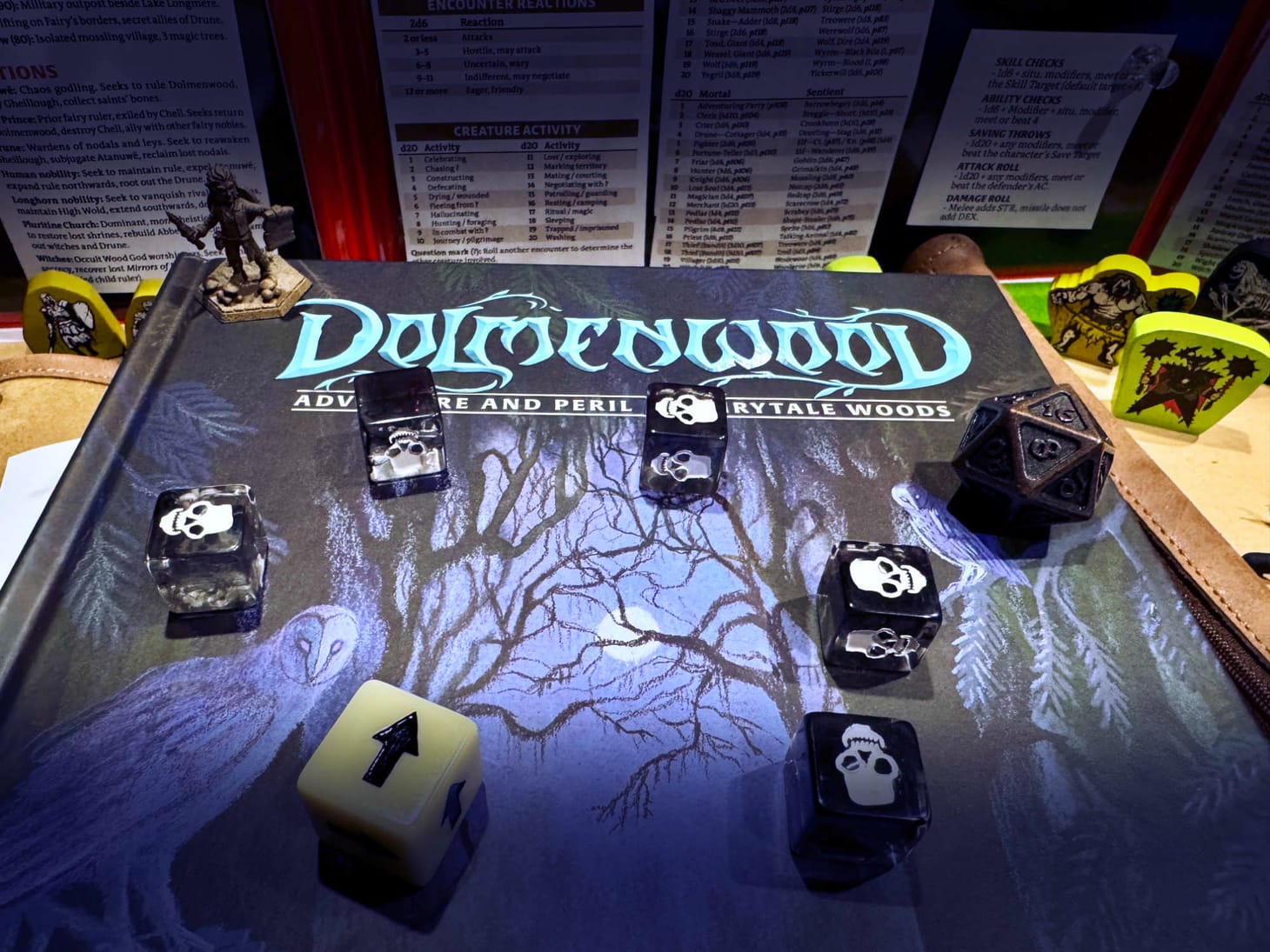

The reason this is on my mind today is that I’ve been workshopping Gavin Norman’s Dolmenwood. I’ve got the (big, beautiful) books stacked up on my little table in the basement and I’ve made a group of five characters. I’m exploring the world, learning the rules, and trying to figure out what’ll really make this game sing.

I was a little surprised, you see, by how much procedural stuff has been going on in my Dolmenwood workshop. This is not a criticism or even a complaint, but it’s the main thing I’m noticing after playing a few sessions. My characters have been traveling in the world and I’ve spent a lot of time making use of the systems for traversing hexes, camping, hunting, foraging, getting lost, cooking, sleeping, gathering firewood, encountering animals, and so on and so forth. This is not what I expected, but I assume that it’s just because I didn’t know much about the books before they arrived.

And so, observing all the time I’m putting into these process, I ask – What does that tell me about the artist’s (Mr. Norman’s) ideas about the game? Probably he considers all this minutiae to be part of the fun. He’s certainly devoted a lot of real estate in the books to this stuff.

And I notice he’s been similarly detailed about other aspects, not just these rules. I’ve heard a couple of podcasters point out the list of beverages you might find at different taverns throughout Dolmenwood. And there’s that magnificent, gigantic campaign book, with one large page devoted to every single hex on the map.

Perhaps, in Mr. Norman’s version of the game, the details really matter. Maybe survival in the wild, as described and shaped by all these little sets of rules, is meant to be one of the predominant experiences of the game. Maybe I’ll lean into it and see what happens if I really focus on that part of it for a while. Maybe the experience I have going through the procedures – step by step, carefully and considerately – will mirror the characters’ experience of cautiously making their way through the dangerous and ever-changing environment(s) of Dolmenwood.

Of course, when you play Dolmenwood, you get to make your choices about which rules to use or abuse or completely disregard. You could hand wave all the travel stuff and just get to the plot.

The World of the Game

One thing that’s abundantly clear is that the world building in Dolmenwood is one of the great joys of the game. We sometimes assume that designing and describing a fantasy world is an essential part of playing any role playing game, but it’s simply not true. There are plenty of games that, for example, rely on knowledge that the players’ bring to the table and, therefore, don’t spend much time on describing the world.

Here, again, we insert the note that every game is different at every table. If I talk about Daggerheart, I’m talking about my experiences of Daggerheart. If I talk about Crown & Skull, I’m talking about the version of it that I have played, at a particular set of tables, with a particular set of people. You need to insert that phrase – “my own experience of” – before every game title I use here.

I’ll use Shadowdark as an example. I’ve played a fair amount of it, and (in my experience of it) there has been relatively little time at the table spent on describing the specifics of the world. Maybe that’s because the person running the game can save time (and cognitive load) by assuming that everyone at the table has relatively similar ideas about what a generalized, medieval fantasy world is like. (The specifics of the environment in Shadowdark matter a lot more, but that’s a different part of this conversation.)

I’ve been running Voidheart Symphony at home and at conventions this year. I don’t spent much time at all describing the world because I can just indicate that it’s a kind of generically urban, American landscape. Most everyone can imagine such a thing, even if they don’t have much real-life, in person experience of it.

This is interesting, though. It brings up a question. Just because I’m not spending time describing the setting, does that mean it’s not one of the dominant elements of the game? Right now I’m thinking – No, the lack of time spent on it doesn’t necessarily mean it’s not important. But I find it hard to believe it’s one of the 2 or 3 most important elements of the game session if you’re really not making time for it. We’ll see. We’ll have to pressure test that idea.

Well so, back to Dolmenwood. Clearly the unique setting that Mr. Gavin’s created is one of the predominant elements. That’s important and useful to take note of. In my sessions, in between all the protocols for getting around in the world, I’ve been taking huge amounts of delight at each person, place, and thing my characters encounter. The descriptions and suggestions in the books are detailed, surprising, and always entertaining. I find myself muttering, “Wow, that’s amazing,” again and again. Seriously, just reading these books has brought me tremendous amounts of joy.

I think I just found the thesis.

So → I’m taking the lesson, as the person running the game, that if I want players to experience the essential Dolmenwood-ness of the Dolmenwood game, I ought to be taking every opportunity to emphasize the particulars of the world. For example, if the characters are out on the road and they encounter an NPC, it would be a missed opportunity if I just described that NPC in a generalized, medieval fantasy sort of way. That’s always a missed opportunity, but especially here in Dolmenwood where everything and everyone you describe is an opportunity to sprinkle some of that wonderful Dolmenwood fairy dust.

In our gaming sessions, we don’t have time to describe everything in detail. We’re always making choices about what parts of a game to linger on and which parts to de-emphasize, both in terms of the story and the mechanics. So it would be very advantageous to have a clear idea of which elements are most useful in bringing out the best in (your own particular experience of) a game. Hmmm – I think I just found the thesis.

Knot Hollow RPG Workshop Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.